Understanding the Role of Human Factors in Railway Inspection

Presenting experts at Wheel/Rail Interaction 2022 made it clear that there’s more to inspection than meets the eye. Education and training can help reduce errors and improve inspection efficiency.

By Bob Tuzik

“Human Factors” are frequently cited as cause codes in railway incidents and derailments. But while track and mechanical inspection processes have evolved, the underlying causes of human error in the railway industry are not well understood. In fact, human-factor-related train accidents per million miles have increased over the past 10 years, said Randall Jamieson, a Principal at Atticus Consulting Group LLC. (See Using Derailment Findings to Identify Derailment Risks.)

Jamieson and Daniel Smilek, a Principal at Atticus Consulting Group and professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the University of Waterloo, where he heads the Vision and Attention Lab, provided their unique perspective on the role of human factors in inspection errors or failures, the limits of human cognition, and how these limitations contribute to errors and accidents in the rail industry at the 2022 Wheel/Rail Interaction conference. Using demonstrations to illustrate scientific findings in the field of cognitive neuroscience, they provide an eye-opening overview of the mechanisms of attention and perception that are relevant to track and mechanical inspection, including phenomena such as “inattentional blindness,” the “vigilance decrement” and “satiation of search.”

“Human factors” is a nebulous term in the railway industry. The underlying root cause of the majority of rule violations, inspection errors, and train accidents can more aptly be called “human attention,” Jamieson said.

Attention errors are very common. “They happen often, and not just to the ‘bad apple’ employee, but to all of us all the time in many different ways,” Jamieson said. So often, he said, that we don’t even notice our little mistakes, lapses of attention, or slips. And if we do notice them, we don’t dwell on what the error was or why it happened. “That’s a big problem in our industry,” he said. “An examination of five years of incident data at a west coast railway, for example, indicated that 93% of the incidents were identified as rule violations by the local officers conducting the investigations. After going through the data, we determined that 67% of all the rule violations actually had an attention-related error of one kind or another as a root cause.”

And what’s the corrective action for a rule violation in which inattention is identified as the root cause, Jamieson asked? “Typically, the offender gets disciplined through time off, or gets fired. Neither of which address the attention-related error,” he said.

Atticus Consulting also looked at a swath of red signal violations on an east coast railway. Similarly, it found that 91% of the incidents were identified as a violation of an operating rule or procedure. A deeper dive indicated that 80% of the incidents were, actually, specific attention-related errors.

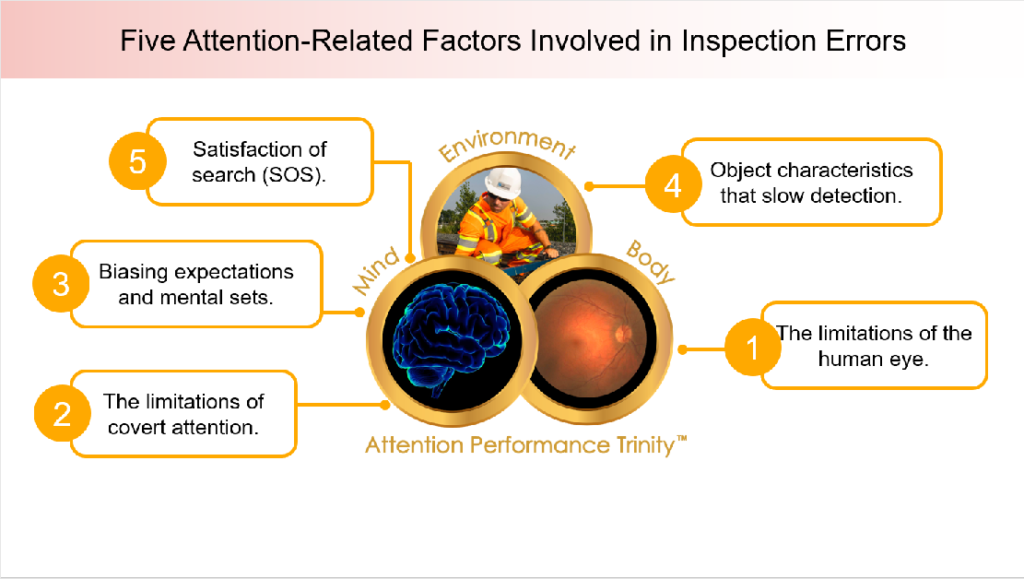

Daniel Smilek identified five primary attention-related factors that are involved in inspection errors:

“To really appreciate these factors, we have to understand that human attention performance isn’t something that just happens in your head,” Smilek said. “In fact, it involves three interrelated components – the mind, body, and environment – which we refer to as the ‘attention performance trinity.’”

The body component begins with the limitation of the human eye. “If your experience is anything like mine, you would probably say that you have a very high definition, very detailed, very clear image in your mind,” Smilek said. “It’s edge to edge, like you’re playing a high-definition movie all the time. And it comes with surround sound, because you hear everything that’s going on. It’s very high definition, and it implies this idea that our brain is processing all the visual information out there and giving us this conscious experience.”

Smilek then conducted a demonstration with a series of photographs that illustrated the limitations of what we actually discern and compute. The demonstration, which illustrated something referred to as ‘change blindness’ showed that we process a lot less information than we think, and that the experience we have of the crystal clear, edge-to-edge movie playing in our heads is something that is known as “the grand illusion of perception,” which is constructed by the brain.

The “grand illusion of perception” can lead us to be overconfident in our perception. And that can lead us to make errors. “It’s very important for people who are involved in inspections to understand these limitations so that they don’t become overconfident in their ability to detect changes,” Smilek said. It’s also important to understand that when a colleague misses an exception or change in continuity, it’s not because he or she is some sort of ‘bad apple’ colleague, it’s because they have a limitation that we all share.

Another limitation, known as “covert attention limitation,” relates to the fact that just because you’re looking at something doesn’t mean that you are going to “consciously” see it. “That’s because your brain can only process a subset of all the information that’s coming from the retina,” he said. The process of selecting that information is called covert attention. “You can think about it metaphorically, like a spotlight shining on one or two objects and selecting them for further processing,” he said. “If you’re looking at a rail, for example, an inspector might fixate on a loose or missing bolt and some other aspect or subset of that. Studies have shown that you’re able to select one, maybe two objects, depending on how those objects are related, for covert attention at any given moment. That means that the things that are not selected by covert attention are not being processed to conscious awareness, so you could miss those completely.” If you’re not covertly attending, you will not be able to see the object. This is referred to as “inattentional blindness.” “So even though you’re fixating on something, you’re not really attending to it, and therefore you don’t consciously see it.”

Going back to the rail with the missing bolt: “Assume that you have selected it with your fixation, then something comes to mind,” Smilek said. “Well, it turns out that that same ‘covert attention’ that is needed to focus on the bolt is also required to bring your thoughts into consciousness. And as covert attention is a limited resource, something has to give. There may not be enough resources left to perceive what’s right in front of you,” he said. “That’s when you fail to see, and you make an error. When our attention is turned inward, which we typically call mind wandering, we can become functionally blind, which is why it’s called ‘inattentional blindness.’”

Visual inspection is also influenced by your mental set, expectations, and prior knowledge. Expectation bias of what you’re going to explore can lead to errors. It can also help “experts,” who know exactly what they’re looking for. But there’s also the chance that defects or flaws are missed because they’re not exactly what the inspector was looking for. “Expertise is a double-edged sword,” Smilek said.

Target prevalence is another factor. When a target is infrequent — present only 2% of the time — people miss that target nearly half the time. This means that uncommon defects are more likely to be missed. Another parameter, ‘satisfaction of search’ indicates that inspection becomes less effective after a salient defect has been found. All of which is to say that what we perceive during the inspection process is tricky business with a plethora of opportunities for error. Or, as one conference delegate put it during the Q&A session following the presentation: “That was fascinating and completely frightening all at the same time! Having identified these five things,” she asked, “what do we do about it?”

“The short answer is education and training,” Randall Jamieson said, “It’s important for employers, leaders, managers, and inspectors to understand more about the factors that either increase or decrease attention performance. If you are armed with some attention strategies that you can apply and practice, you can reduce the likelihood that you’re going to have attention-related errors.”

Bob Tuzik is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Interface Journal.

This article is based on a presentation made at Wheel/Rail Seminars’ 2022 Wheel/Rail Interaction conference.