The truck bolster bowl: Is it a bowl or a bearing?

by Gary Wolf • October 2005

Like many aspects of the three-piece truck, performance issues surrounding the truck bolster bowl and body centerplate are often misunderstood. One of the biggest misunderstandings is that the bolster bowl is actually a bearing. Years ago at a meeting where truck performances issues were being debated, an especially astute engineer from one of the car builders made the simple statement: “We keep calling it a bowl, when in reality it is a bearing. And what do you do with a bearing? You lubricate it!” That simple, yet profound, statement contained much wisdom.

Car designs reaching back to the 1800s all had some semblance of a bolster pivot, or center bearing. Initially quite small in diameter, as the size and weight of freight cars increased, the size of the bearing surface gradually increased. Today, most centerbowls are either 14 inches or 16 inches in diameter. The function of the centerbowl is twofold: 1) To distribute the weight of the car body into the truck bolster. 2) To provide a central pivot point for the truck bolster to turn on the car body.

When a car is loaded to a gross rail load of 286,000 pounds, there is approximately 246,000 pounds of weight that bears onto the two truck bolsters. Since there are two bolsters, simple math tells us that each bolster must support roughly 123,000 pounds. If the body centerplate is nominally 16 inches in diameter, the stress per unit area is approximately 600 psi. Further, if the body centerplate must rotate within the bowl, the turning moment of two surfaces in contact is defined mathematically as:

Centerbowl Turning Moment = R (2/3) µ (N) Where:

R = radius of the centerbowl

µ = coefficient of friction between the centerplate and centerbowl

N = Normal force on the centerbowl

If we assume that µ is 0.40 for a dry bowl condition, and the normal force in the bowl is roughly 123,000 pounds, then for an 8-inch radius centerbowl, the turning moment would be approximately 260,000 in.-lbs. The steering moment generated by the wheelset radius differential must overcome this substantial turning moment in order to turn the bolster on the body centerplate, and steer the truck through the curve.

If we consider the condition of a lubricated centerbowl, with a µ of 0.10, then the turning moment drops to roughly 65,000 in.-lbs., and the required steering moment drops accordingly. AAR interchange rule 47 requires that any car on a repair track that is raised off the trucks must have the centerbowl lubricated with either an AAR-approved lubricant or an approved centerbowl liner. It is easy to see why centerbowl lubrication greatly improves the steering ability of the truck by a reduction in rotational resistance. Rail Sciences’ field testing has shown that a dry centerbowl can increase turning moment by approximately 50% above a nominally lubricated centerbowl.

Effects of Wear

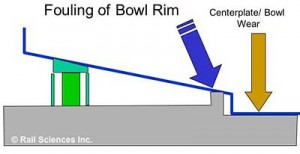

This analysis assumes that there is an even distribution of vertical load across the surface of the centerbowl. This may not always be the case. If there is substantial wear on the surface of the centerbowl, or corresponding wear on the surface of the centerplate, then the centerplate will naturally sit deeper in the centerbowl. In cases of extreme wear, this will cause contact to occur around the rim of the centerbowl and against the base of the body centerplate. This condition is illustrated in Figure 1. When this occurs, the turning moment radius is moved to the extreme radius of the centerbowl rim, and the equation for total turning moment becomes: Centerbowl Turning Moment = R µ (N)

Thus, assuming a µ of 0.40, and a normal force of 123,000 pounds, the total turning moment becomes approximately 390,000 in.-lbs. This is a substantial increase in turning moment of 50%, which can cause the wheelset steering moment to be insufficient to steer the truck bolster through the curve. AAR interchange rule 47 requires that a minimum clearance of 1/16 inches must be maintained between the centerbowl rim and the body centerplate base at all times.

Evidence of rubbing or fouling between the bowl rim and the body centerplate indicates a violation of this AAR rule, and can lead to poor steering, truck warp and excessive gauge spreading forces at the wheelsets.

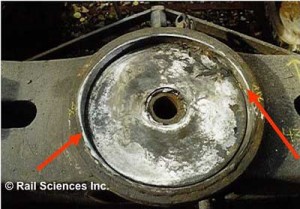

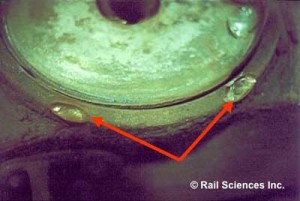

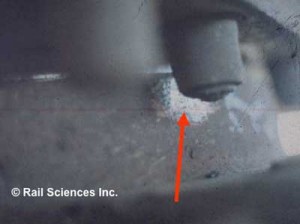

Figure 2 shows evidence of fouling on the centerbowl rim. Figure 3 shows an extreme example where fasteners used to secure the centerplate to the body bolster have dug into the rim of the bowl preventing proper truck rotation. Another condition that can increase turning moment is where fasteners used to connect the body centerplate to the body bolster foul, or rub against, the outer rim of the centerbowl. Figure 4 shows an example of Huck bolts rubbing a shiny mark into the edge of the centerbowl rim, greatly increasing the truck turning moment.

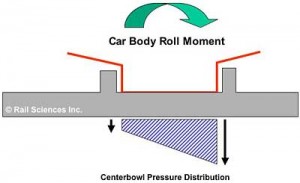

During curving on superelevated track, a roll moment of the body centerplate can cause an unequal pressure distribution on the surface of the centerbowl. Figure 5 illustrates this condition.

When this occurs, the turning moment is substantially increased as the effective turning radius is moved toward the outer edge of the centerbowl. Tipping of the car body can also move the centerplate into edge contact with the vertical surface of the centerbowl, further increasing turning moment. Thus, operation of high center of gravity cars on over-elevated curves or below balance speed can affect the ability of the cars to effectively steer through the curve. Also, operation through spirals with significant track twist can produce a similar effect. Testing by Rail Sciences has shown that the effect of simulated track twist can increase turning moment by 100% to 200%, depending on the severity of the twist.

In order to reduce the chance of increased turning moment and rotational resistance, AAR rule 47 lists several dimensional tolerances and maintenance requirements for the centerbowl and centerplate. In summary, these are:

• 1/16-inch clearance must be maintained between the centerbowl rim and the base of the body centerplate.

• The maximum amount of wear in the depth of the centerbowl is 5/16 inches.

• The maximum amount of allowable diameter increase in the centerbowl is 7/8 inches beyond the nominal diameter (e.g., 16-7/8 inches for a nominal 16-inch centerbowl).

• The difference in diameters of the body centerplate and the bolster bowl must not exceed 1-3/8 inches (check both fore and aft, and side to side).

• Body centerplate diameter must not be reduced more than 1 inch (Rule 60)

• Top surface of the bolster bowl rim must not be in contact with the centerplate horizontal surface.

• Lubrication or a lubricating liner is required any time a car is on a repair track and the car body is raised off the trucks.

Those responsible for maintenance should become familiar with these requirements for the centerbowl and centerplate. Excessive truck turning moment can be the root cause of excessive wheel flange wear, and even gauge-spreading or rail rollover derailments. In order to improve overall performance, maintenance managers must start thinking of the centerbowl as a bearing, and ensure that it is properly lubricated during any maintenance activity.